Barbados: A Walk Through History (Part 17)

Section 9 Trident’s Promise & Independence (Cont’d)

(Barbados’ Father of Independence: Errol Barrow)

Adams vs. Barrow

Errol Barrow joined Grantley Adams’ Barbados Labour Party (BLP) as soon as he returned to Barbados. He was elected into the House of Assembly the following year, 1951.

There is no doubt that Adams’ early political success at age 31, immediately upon returning to Barbados, is due to his praiseworthy deeds in Britain during and after WWII. However, the fact that Charles Duncan O’Neal, the founder of the Barbados labour movement, was his uncle, and that Adams’ right-hand man, Hugh Cummings, was his cousin, speaks for itself.

Nonetheless, it did not take long for Barrow to realize that his ideal vision of an independent Barbados, formed when he was studying in the UK with other men with similar ideals from British colonies, did not align with those of suzerain-centered BLP leader, Adams.

There are some anecdotes which depict the extent of Grantley Adams’ conservative views.

After WWII, voices were growing in the newly-formed United Nations for de-colonization. Britain, who was skilled at swaying international opinion, came up with the idea to use a Black man of colonial birth to justify the UK’s colonial policies. The man they selected was none other than Grantley Adams. Adams was one of the first Black people to speak to the UN as a member of the British delegation to the UN in 1948. However, his speech attracted heavy criticism from independence activists all around the world for defending Britain’s colonial ruling system (note 1).

In 1953 the leftist “People’s Progressive Party” (PPP) of British Guiana (present-day Guyana) overwhelmingly won the election and was poised to take power. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was concerned that the colony was heading down a path towards communism, and suspended the colonial constitution and deployed military intervention. Cheddi Jagan and other senior PPP members were ousted, and an interim government was created. One of the expelled PPP members was a fellow student of Errol Barrow at the London School of Economics - Forbes Burnham. After the PPP was overthrown by the British government, Grantley Adams sent a telegram back to the suzerain relaying the following message:

“Our experience of Jagan and his sympathisers leads us to feel that the British West Indies is likely to be harmed by that sort of person. However much we must regret suspension of the constitution, we should deplore far more the continuance of a government that put communist ideology before the good of the people.” (note 2)

After the Barbados House of Assembly elections of 1951, friction emerged in the ruling BLP between the elder senior members, such as Grantley Adams, who did not make clear their attitude on independence, and the young progressives, led by Errol Barrow, who wanted early independence from Britian.

In early 1954, Barrow announced his split from the BLP, and the following year he created the Democratic Labour Party (DLP) together with 26 comrades including T.T. Louis, James Cameron Tudor, and Frederick Smith.

(Prime Minister of the Federation of the West Indies, Grantley Adams)

While still under colonial rule, Barbados gained its own cabinet system in 1954, the same year that Barrow and his comrades rebelled against the BLP. The Cabinet was comprised of the “Executive Committee” members who were given the official title of “Minister”, and the leader of the Cabinet was called the “Premier”. Thus, Barbados became the only self-ruling British colony in the West Indies to have a Premier at this point in time. The first Premier of the Colonial Government was Grantley Adams.

One can see that behind this movement was the Governor’s “guidance” on the local level in implementing the British suzerain’s far-sighted plan. Britain tried to preserve a peaceful hold on power while preventing radicalism and leftism in Barbados and other West Indies colonies, having in mind the experience in British Guiana the previous year.

Britain, at this point, was trying to stop its Caribbean colonies from becoming completely independent and to confine them to the status of “dominion”, which the British government was able to exercise a fair amount of control over (note 3). With this in mind, it makes sense that Barbados, where Britain’s influence was so strong that it was nicknamed “Little England”, and whose government was stable compared to other colonies in the region, was the first colony in the West Indies to become a self-ruling colony.

Adams’ appointment as Premier of Barbados’ self-government marked the peak of his political career. Adams’ BLP won a sweeping 15 out of 24 seats in the 1956 House of Assembly election, while Barrow’s DLP which split from the BLP, only held four seats, with Barrow himself failing to get elected. In the election two years later to fill a vacancy, Barrow bounced back in the House of Assembly, but the strength of the newly formed DLP was far from overpowering that of the BLP. On the other hand, Adams, who was appointed to a second term as Premier, was knighted by Queen Elizabeth in 1957.

It seemed as though Adams’ status as a leader was unshakeable. However, it is at this time that he made a crucial mistake in assessing the state of affairs. While Adams was fulfilling his appointment as Premier, he left Barbados to become the Prime Minister of the Federation of the West Indies, which was founded in 1958.

Let me expand on the Federation of the West Indies.

I previously mentioned in Section 8 that in the latter half of the 19th century the “Confederation Crisis” sent Barbados into an uproar. Following this, the discussion of forming a “confederation” or “federation” was taken on and off the table several times. In 1884, after the “Confederation Crisis” of 1876, the power-wielding sugar industry farming association in Barbados made a rather bold suggestion on the island’s joining the Dominion of Canada (,though this idea immediately faltered and subsequently disappeared).

Since modern times, conflicted feelings were continually present among the small islands of the British West Indies, for whom it was no easy feat to become politically and economically independent, of whether or not to join hands with fellow islands in the region or to remain solo. However, in reality, although they were all British colonies, every island had its differences in respect to its history and systems, racial and ethnical composition, customs, etc. Additionally, while they were connected by the sense of victimization of being colonized, there were also feelings of rivalry between the islands, and instances of trying to undermine each other out of jealousy made it difficult to unify these islands. This “West Indies mentality” was sometimes used by the British government as an effective tool to rule and control these colonies.

The budding concept of the West Indies Federation was visible from the 1930s when influential people in Jamaica, Trinidad, Dominica, Grenada, Barbados, and others thought to come together to wage a regional front to expand their political autonomy from Britain. At first Britain did not take the threat of the islands creating a united front seriously; however, it gradually became warier of potential radicalization of those islands.

This was right at the time of WWII, and discussion of a federation faded in and out. However, in 1947, in order to gain control over the situation, the British Colonial Office held a conference with representatives of its West Indies colonies in Montego Bay, Jamaica, where the pros and cons of establishing a federation were debated. The representative from Barbados was Grantley Adams, who strongly empathized with the concept of a federation.

In the 1950s the movement to form a federation started to gain traction with two major British colonies, Jamaica and Trinidad, leading the movement. Britain thought that it was not in its best interest to try and forcibly stop the formation of a federation, and so a conference of West Indies’ representatives was held in London in 1956 where the establishment of a federation was unanimously agreed upon. During this process, Britain relied upon the seemingly moderate and loyal Grantley Adams and Jamaica’s Norman Manley (note 4).

This is how British colonies in the Caribbean (with the exceptions of British Guiana (current Guyana) and British Honduras (current Belize)) came together to establish the Federation of the West Indies.

However, just when it seemed to be smooth sailing, friction started to occur between Jamaica and Trinidad. These two colonies, who were “leaders of the English-speaking West Indies”, were fighting over whether the seat of the capital of the Federation would be in their respective island, each unwilling to concede to the other.

Britain, in order to lend a “helping hand” to the smooth establishment of the Federation, created a “British Caribbean Federal Capital Commission”, and placed Francis Mudie, an experienced colonial officer, in charge of the head of the Commission (note 5).

Mudie’s first candidate for the capital of the Federation was neither Jamaica nor Trinidad, but in fact Barbados. His choice was Britain’s solution to softening the tension that had built up between Jamaica and Trinidad.

This displeased both Jamaica and Trinidad. Mudie’s proposal was harshly criticized by Morris Cargill, a well-known newspaper columnist of Jamaica, who wrote that “Barbados did not belong to the West Indies in spirit…[that] it was vitiated by class and colour prejudice and [that] it was the world’s largest naturally occurring septic tank.” (note 6). As I personally spent time in Barbados I strongly disagree with this criticism. But, on the other hand, this example gives a glimpse of how “Little England” was perceived by her envious neighboring islands.

After a long bout of arguments, Chaguaramas, Trinidad, was decided upon as the capital of the Federation, and in 1958 the West Indies Federation was officially launched. Its members were the ten British overseas territories -- Antigua, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, Jamaica, Montserrat, St. Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla (note 7), St. Lucia, St. Vincent, and Trinidad and Tobago.

The Federation was, however, dysfunctional from the start. Unfortunately for the Federation, major players such as Trinidad’s Eric Williams and Jamaica’s Norman Manley were swamped with their respective island’s political wranglings and were not able to fully take part in the Federation’s operations. Then entered the man portrayed as a savior of the Federation and its first Prime Minister, Grantley Adams of Barbados.

However, since the Governor sent from Britain’s Colonial Office held more power than the Prime Minister of the Federation, internal power struggle was never-ending. Efforts to reach an agreement were abortive on basic issues such as freedom of movement within the Federation, customs tariff between islands, etc.

In the end, Jamaica left the Federation in 1961, and Trinidad followed suit the following year. The West Indies Federation disappeared into thin air only four years after its inauguration. On August 6th, 1962, Jamaica gained independence from Britain, and on the 31st of the same month Trinidad and its small neighbor Tobago came together and gained their independence, forming a new nation, Trinidad and Tobago. These were the first two nations of the British West Indies to become completely sovereign from their suzerain.

Grantley Adams was the one who drew the short straw in this situation. During the startup of the Federation, he relinquished his post as Barbados Colonial Premier to his comrade Hugh Cummings and traveled to Chaguaramas to take up the position of Prime Minister of the West Indies Federation. Adams did his best to try and extend the life of the Federation from its malfunctional beginning, but while he was away from Barbados, the DLP, led by Errol Barrow, was steadily gaining power. The unemployment rate within Barbados had soared to around 20%, with many citizens choosing to migrate to the UK, US, Canada, and other countries in order to provide for their families. Adams’ involvement with the ill-fated West Indies Federation caused the popularity of his BLP to decrease significantly.

In 1961, while Adams was away in Chaguaramas, Barbados’ House of Assembly election was held which resulted in the DLP gaining a majority over the BLP, ousting the BLP from its position of ruling party. After the failure of the Federation of the West Indies the following year, Adams returned to Barbados only to find himself without any official position. Adams’ involvement with the “controversial issue” – the Federation- had caused him to lose his seat of power within Barbados itself.

Trials and Tribulations of the Little Eight: The Concept of the Eastern Caribbean Federation

Needless to say, the political figure to become the next Premier of Barbados after the rise of the DLP was its leader, Errol Barrow.

Immediately after assuming office, Barrow proactively poured public investments into infrastructure such as constructing roads and improving sewage and water facilities. By increasing effective demand, the island’s economy got back on its feet, allowing Barrow to concentrate on reducing the unemployment rate. The effects of Keynesian economics, popular during this time and which Barrow most likely studied during his time at the London School of Economics, were evident in his early policies. Additionally, Barrow started to put effort into policies promoting inbound tourism, first of all from Britain, in order to free the island from the sugar industry’s grip. In addition to the above changes, Barrow’s efforts to ensure free public education, provision of school lunch, implementation of a national health insurance scheme as well as workers’ compensation system, etc. gained the support of the masses, solidifying the energetic Barrow’s status as a national leader.

I previously mentioned that after the failure of the West Indies Federation, Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago gained their independence from Britain in 1961 and 1962, respectively. In comparison, Barbados did not gain its independence until 1966. So the question arises that why, although Barrow’s DLP specifically mentioned independence in its manifesto upon the 1961 election, did it take longer for the more politically and economically stable Barbados, who was on good terms with Britain, to break free from its suzerain?

In fact, the movement to create a federation did not completely fade away when Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago left the scene. After those two “big powers” in the region exited, the “Little Eight”, which was comprised of the remaining eight British colonies, including Barbados, they began to search for a viable way to create the new “Eastern Caribbean Federation”.

Needless to say, becoming an independent state is more complicated than just signing a few documents. Legislative, judicial, and executive powers must be appropriately constructed, the government must make sure that its people are fed, it can collect taxes, maintain public security, establish diplomatic relations with foreign countries and open embassies in those countries, and mobilize military forces to defend itself from foreign enemies (, although there exists a unique independent country that has a tenet in its Constitution pledging “land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained”…).

It required a vast amount of courage for the islands of the Little Eight to proceed to independence separately. Their incomes up to this point had come almost solely from the sugar industry, and their small populations - tens to several hundred thousand people - meant a lack of human resources.

Due to the above obstacles, the Little Eight still hoped for the “Eastern Caribbean Federation” to succeed, and each colony hesitated to seek individual independence until the last moment. Barrow, who led Barbados to its independence, stated the following in 1962:

“Anyone who does not understand the economic, political and geographical background of the West Indies will not readily appreciate why these islands should want to come together in a federal system of government. If there were one area which a federal system of government eminently suits, it is the eastern Caribbean…We are therefore bound together by some times of consanguinity, it is true, but we are bound together by similar conditions and similar economic backgrounds more than anything else.”

The attempt by the Little Eight to form the Eastern Caribbean Federation started in the beginning of 1962 when it was clear that Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago were to leave the West Indies Federation. Representatives of each colony gathered together multiple times with Reginald Maulding, British Secretary of State for the Colonies, to discuss how to bring the concept of the federation to life. Through the meetings, they agreed that the federal capital would be located in Barbados, that citizens would be able to move freely between colonies within the federation, and that a customs union would be implemented. They were even able to draw up a draft constitution of the federation.

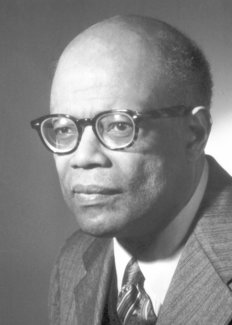

The brain behind the theoretical facets of taking the concept of the federation and making it a reality was Arthur Lews, a St. Lucian born development economist and professor of the University of West Indies. Lewis’ astonishing speed in writing and handing in paper after paper for the repeated meetings with Secretary Maulding was well-known. Lewis went on in later years to take up teaching posts at Princeton University, eventually proceeding to become the founding President of the Caribbean Development Bank. In 1979 he won the Nobel Prize in Economics, making him the first Black recipient of a Nobel Prize apart from the Peace Prize (note 8).

What put a spoke in the wheel and ultimately caused the downfall of the federation (which initially was thought to be off to a favorable start due to outstanding Arthur Lewis’ involvement), was in fact a matter of money.

The Little Eight had expressed their hope that five years out from the inauguration of the Eastern Caribbean Federation that Britain would gratuitously continue to provide economic aid to help stabilize the federation’s financial footing. However, no matter how long they waited, the British government did not respond. It took two years for Britain to finally give its official reply. Those two years proved to be fatal for the Eastern Caribbean Federation. When embarking on an important endeavor, there are cases where it is considered better to not think too deeply and just head out at full speed. As such, the federation endeavour lost its momentum during the two years it spent mulling over its future.

During this time, Grenada, Antigua, and Montserrat grew frustrated and suspicious of Britain’s “goodwill”, and subsequently left the federation project. Confrontation over opposing opinions of the five remaining colonies arose. Eventually at the meeting in April 1965, John Compton, representative of St. Lucia, called into question Barbados’ level of enthusiasm into the federation, resulting in a heated argument with Barrow, who ultimately left the meeting in anger (note 9).

This was the last meeting held between the islands regarding the federation, crushing any hopes of establishing a united front. Considering the result from the perspective of Barbados gaining an early independence from Britain, the three years from 1962-65 were a lost time not only for the island, but for Errol Barrow as well.

(Sir Arthur Lewis, Recipient of the Nobel Prize in Economics)

The collapse of the concept of the Eastern Caribbean Federation meant that Barbados’ only option was to rely solely on itself in order to break free of Britain’s rule.

The Barbados Colonial Government, with Barrow as its Premier, published a white paper in August 1965 titled “The Federal Negotiations 1962-65”. The paper proposed Barbados make the choice of separate independence as the result of the failure to establish the Eastern Caribbean Federation.

The proposal was approved by both Houses of the Barbados Parliament, and the Parliament proceeded to request a meeting with the suzerain Britain’s Frederick Lee, Secretary of State for the Colonies. In response, the “Barbados Constitutional Conference” was held at Lancaster House, London, in June 1966. Representatives from three of Barbados’ political parties (Democratic Labour Party(DLP), Barbados Labour Party (BLP), and Barbados National Party (BNP) (note 10)) who held seats in the House of Assembly participated in the Conference. Incidentally, Secretary Lee was the last person to hold the position of Secretary of State for the Colonies, as the Colonial Office closed its doors in August the same year, putting an end to its long history.

A draft constitution, prepared by the Barbados Colonial Government, was under deliberation at the Lancaster House conference. The framework for the Constitutional Monarchy of Barbados, which lasted from the time of its independence up until 2021, was put in place during this conference. The framework showed that while Barbados was an independent sovereign state, possessing its own legislative, executive, and judiciary branches of government, it was a member of the British Commonwealth, and that it was to take its first steps as such within the Commonwealth Realm, with the monarch (Queen Elizabeth II at the time) as Head of State. The post of Governor-General was established as the representative of the British monarch. Additionally at the conference, the date of independence was set for November 30th the same year.

The Commonwealth is the term for one of the forms of the loose confederation of Britain and its former colonies, which in the late 19th century started to gradually gain independence from their suzerain. Within the Commonwealth countries are nations that keep the British King (or Queen) as their Head of State – the collective term for such countries is the Commonwealth Realm.

Barbados became the 26th Commonwealth nation when it gained its independence; other countries in the Commonwealth Realm at that time included Australia, Canada, Ceylon (current Sri Lanka), Gambia, Guyana, Jamaica, Malta, Sierra Leone, and Trinidad and Tobago (note 11). On the other hand, countries in the Commonwealth who were not part of the Commonwealth Realm, in other words countries who became republics, were Ireland, India, Pakistan, Singapore, Kenya, Ghana, Nigeria, the Republic of South Africa, and others (note 12).

On November 3rd 1966, after Barbados’ new configuration was settled upon at the conference at Lancaster House, the last House of Assembly election of the island’s colonial period took place. Errol Barrow’s DLP won 14 out of 24 seats, making it again the party in power. This election secured Barrow’s position as the first Prime Minister of independent Barbados. On the other hand, the BLP won eight seats. Grantley Adams was one of the assemblymen to be voted in, marking his re-entry into the political scene of the island four years after being out of the spotlight since the collapse of the Federation of the West Indies.

Final preparations to the legal framework necessary to implement Barbados’ independence picked up speed once the elections had ended. On November 17th, the British Parliament adopted the “Barbados Independence Act”. The official name of the Act, whose contents stated that the suzerain Britain granted Barbados its independence, and that the Barbados Constitution would become effective on November 30th, was “An act to make provisions for, and in connection with, the attainment by Barbados of fully responsible status within the Commonwealth”. Five days later on November 22nd, the “Barbados Independence Order” was put into effect by Queen Elizabeth II, which ordered the Act to be executed on November 30th.

Independence Ceremony at Garrison Savannah

Barbados was the fourth country in the English-speaking Caribbean to gain its independence, following Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, and Guyana (previously British Guiana).

The long-awaited independence ceremony was held on November 30th, 1966. Although rain threatened to put a damper on the day’s events, thousands of people crowded around the venue, Garrison Savannah, and calmly watched the events take place.

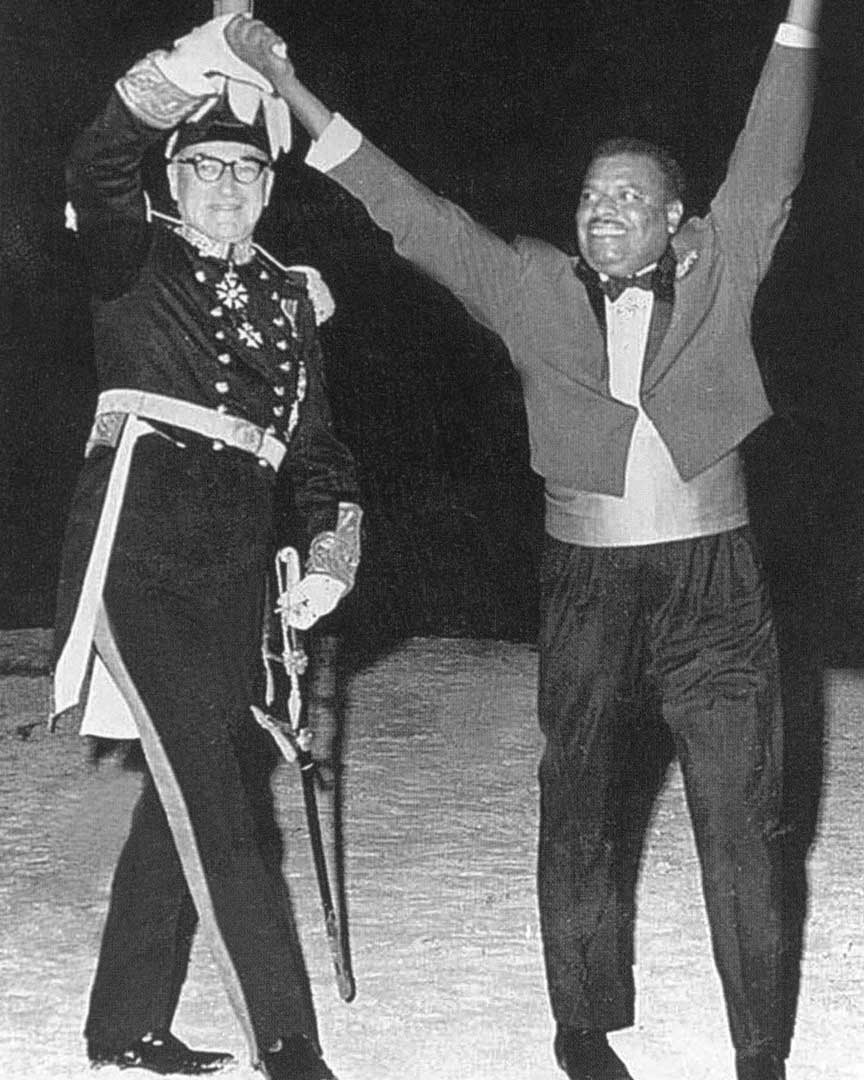

Attendees of the ceremony included first Prime Minister of independent Barbados, Errol Barrow, the last colonial governor Sir John Stow (note 13) as well as Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, representing Queen Elizabeth II of Britain, Barbados’ previous suzerain.

Barrow addressed the Duke of Kent with the following message:

“This is a very proud moment in the history of the people of Barbados. I am glad, and I am sure the members of my Government are equally glad, that we were born at a time when we could see this eventful day. On behalf of the people of Barbados, on behalf of the Government, on behalf of the young people, I should like you to convey to Her Majesty the Queen the heartfelt thanks of us all that she was on this eventful day the Head of the Commonwealth, and that she elected to send you, her trusted cousin, to see us through the dawn of Independence.” (Note 14)

On this day at 12:01 a.m., the Union Jack was taken down and Barbados’ “broken trident” flag was raised in its place. During the flag raising ceremony, the 46-year-old Barrow stood next to Governor Stow, holding up both hands in celebration of Barbados’ independence, wearing his formal mess dress uniform from his time in the UK Royal Air Force, which along with the contents of his independence speech, signified not only the peaceful attainment of independence from Britain, but also symbolized the understanding that Barbados would be part of the Commonwealth Realm, with the Queen as Head of State.

Despite going through a few post-independence challenges, Barbados continued on the path towards a stable country as a parliamentary democracy. However, it would take another 55 years for Barbados to become a republic with a native citizen as its President, not the Queen of England, a foreigner, as its Head of State.

(The first Prime Minister of independent Barbados, Errol Barrow, and the island’s last colonial governor, Sir John Stow)

A month after its independence, in December 1966, Barbados became a member of the United Nations. This was the time at the height of the Cold War between the Western bloc headed by the United States and the Eastern bloc headed by the Soviet Union. The Cuban Missile Crisis threatening nuclear war occurred only four years before.

Barbados began proceeding as an independent state and a member of the Commonwealth. It's first Prime Minister Errol Barrow’s speech at the UN General Assembly upon Barbados’ inclusion imparted an impression of a strong spirit and pride in its determination towards realistic and autonomous diplomacy of a small but sovereign nation.

“We shall not involve ourselves in sterile ideological wranglings because we are exponents not of the diplomacy of power, but of the diplomacy of peace and prosperity. We will not regard any great power as necessarily right in a given dispute unless we are convinced of this, yet at the same time we will not view the great powers with perennial suspicion merely on account of their size, their wealth, or their nuclear potential. We will be friends of all, satellites of none.”

(To be continued in Section 10: Steps After Independence)

(Note 1) “Reflections on Grantley Adams” by James Dottin, NATION NEWS, April 20, 2012

(Note 2) “Westminster’s Jewel, The Barbados Story” by Olutoye Walrond, P.127

(Note 3) A British dominion was a territory that had a high level of autonomy, but its legal system was governed by the suzerain Britain. This meant that a legislative bill in said dominion could be vetoed at the discretion of the King or Queen of Britain. Canada became the first British dominion in 1867, followed by Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and Ireland.

(Note 4) Norman Manley’s son, Michael Manley, studied alongside Errol Barrow at the London School of Economics, and later became the fourth Prime Minister of Jamaica.

(Note 5) Francis Mudie had yearslong experience in colonial India, and was one of the people who pushed for a separate Muslim-majority Pakistani state when India became independent. Immediately after India and Pakistan became separate countries in 1947, Mudie was governor of West Punjab of Pakistan for two years, although he had been a colonial official of the former suzerain. Afterward, he was the head of the British Economic Mission to Yugoslavia, which although was a socialist nation, had been expelled from the Soviet Cominform and had found itself in a dire situation. During his time there he helped to supply Yugoslavia with weapons needed for warfare. But his homeland’s government decided to send him on a new mission in the Eastern Caribbean after observing the unfolding situation in the region.

(Note 6) “Barbados, A History from the Amerindians to Independence” by F.A. Hoyos, P.228, P.266

(Note 7) Anguilla was placed under the jurisdiction of St. Kitts (St. Christopher) in 1825. In 1967 Nevis joined the two islands to become the British self-governing entity of St. Kitts, Nevis, and Anguilla. However, in 1969 Anguilla became dissatisfied with the St. Kitts-centered policies and subsequently left the entity and became a separate republic. However, Anguilla was suppressed by British security troops, which were dispatched at the request of St. Kitts, and was once again placed under British rule, and to this day is still a British overseas territory.

(Note 8) Sir Arthur Lewis published a paper on various factors that caused to the downfall of the Eastern Caribbean Federation titled “The Agony of the Eight” (1965). He lived his last years in Barbados, where he had worked as first President of the Caribbean Development Bank. He passed away in 1991 at the age of 76 in Barbados.

(Note 9) John Compton, whom Errol Barrow had a heated exchange with, would later become the first Prime Minister of St. Lucia after its independence from Britain in 1979.

(Note 10) Afterward, the Barbados National Party fell from power, and in 1970 the party dissolved. Ernest Mottley, who headed the BNP for years, is the grandfather of the current Prime Minister of Barbados, Mia Mottley, leader of the Barbados Labour Party, who took office in 2018, and became the nation’s first female Prime Minister.

(Note 11) Among those in the Caribbean region, Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago were both part of the Commonwealth Realm upon their independence, but in 1970 and 1976 respectively, they became republics while remaining in the Commonwealth.

(Note 12) Currently (as of December 2023), the Head of the Commonwealth is Charles III, king of the United Kingdom. The Commonwealth has 56 member nations, of which 15 are part of the Commonwealth Realm. There are several nations in the current Commonwealth such as Mozambique (previously under Portuguese rule), Rwanda (previously under German rule, then Belgian trust territory), that had not been under British rule. Among the Commonwealth nations, in order to distinguish between themselves and non-Commonwealth nations, the title of the chief of the diplomatic mission in foreign countries is not called an Ambassador, but a High Commissioner. Accordingly, the site where diplomatic activities are carried out is not called an Embassy, but a High Commission. For example, the building housing the Canadian diplomatic mission in Barbados is called the High Commission of Canada in Barbados, and its chief is called the High Commissioner.

(Note 13) Sir John Stow, the last Colonial Governor of Barbados, retired in May 1967 after the island gained its independence, and in his place a well-known medical doctor and Senator, Winston Scott was recommended by Prime Minister Barrow and appointed by Queen Elizabeth as the Governor General. Scott was the first Governor native to Barbados and with African roots.

(Note 14) Daily “ADVOCATE”, November 30, Wednesday, 1966

(This column reflects the personal opinions of the author and not the opinions of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan)

WHAT'S NEW

- 2025.12.25 UPDATE

PROJECTS

"Barbados A Walk Through History Part 17"

- 2025.12.2 UPDATE

EVENTS

"Pacific & Caribbean Student Invitation Program 2025"

- 2025.10.30 UPDATE

EVENTS

"Support for the 2025 Japanese Speech Contest in Jamaica"

- 2025.10.30 UPDATE

EVENTS

"Invitation Program for the Director of Bilateral Relations of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade of Jamaica"

- 2025.10.16 UPDATE

EVENTS

"421st Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.9.18 UPDATE

EVENTS

"420th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.8.28 UPDATE

PROJECTS

"Barbados A Walk Through History Part 16"

- 2025.7.17 UPDATE

EVENTS

"419th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.6.19 UPDATE

EVENTS

"418th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.5.15 UPDATE

EVENTS

"417th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"