Barbados: A Walk Through History (Part 16)

Section 9 Trident’s Promise & Independence

(National Flag of Barbados)

On November 30th, 1966, Barbados held its independence ceremony in the Garrison Savannah in the outskirts of Bridgetown. The British Union Jack was taken down from the pole, and the national flag of the independent Barbados was proudly hoisted up in its place.

The design of the national flag of Barbados consists of three vertical rectangles—the outer two ultramarine and the middle a golden yellow color. The ultramarine rectangles represent the sky and the sea, and the golden yellow represents the sand of Barbados’ beaches. In the center of the flag is a black trident, whose lower part is designed to look like broken.

Before its independence, Barbados had a “colonial flag”, which combined the colony’s emblem with the suzerain’s Union Jack. The emblem depicted the King (or Queen) of the United Kingdom riding in a carriage drawn by two horses at sea with holding the Roman god of sea Neptune’s trademark symbol, the trident, in his (her) hand.

By depicting a broken trident on the flag, it symbolized the spirit of the newly independent Barbados, throwing off the yolk of 339 years of British colonial rule over the island (note 1).

Barbados peacefully separated from its suzerain without armed conflict or revolution, but instead through the gradual increase of autonomy. However, there were many twists and turns along the way. In this section I will talk about the various movements in the 30 years until independence.

(Barbados’ colonial emblem)

Grantley Adams makes his entrance

The British government established a commission to look into the causes of the turmoil that rattled through Barbados and other British colonies in the West Indies during the 1930s. The commission found that the series of riots was caused by discriminatory social statuses, squalid working conditions, and hardships in daily life faced by the majority of the colonies’ residents—people of African descent. As such, the British government and colonial officials started to present a more tolerant attitude toward residents’ labor union movements and political parties’ activity in order to relieve tensions.

In the year following the “1937 Riots” in Barbados, a new political party named the Barbados Labour Party (BLP) was formed (note 2). Additionally, in 1941 the Labour Union’s united organization “Barbados Workers’ Union” (BWU) was created. These two entities were inseparable from the internal politics of Barbados, and continued to expand for some time.

The person at the center of this movement was Grantley Adams (1898-1971), whom I briefly mentioned in the previous section. He was the deputy party leader of the BLP when it was created, but immediately the following year he became the head of the party, and was the president of the BWU from its founding.

Adams was born to a Black family in the Parish of St. Michael in the south of Barbados. His father was a school teacher. Adams graduated from the prestigious high school Harrison College and went on to earn a scholarship with his outstanding grades to study at Oxford University in England, where he was qualified to practice law. Having returned to Barbados in 1925, he became an active member of the Barbados colonial cricket team (note 3) while practicing law.

It would be a simple story if Grantley Adams, who excelled both in sports and in academics, had wholeheartedly put in effort to fight for improved living standards and expansion of rights for his fellow non-white counterparts from the outset. But history is not so simple.

While studying in Oxford, Adams entered the British Liberal Party (note 4). The Liberal Party was originally a party which was strongly influenced by liberal industrial capitalists, which drew a line with the center-leftist Labour Party and their focus on labor union movements. Adams’ entry into the political world was this bourgeois political party that placed importance on the suzerain Britain’s ruling order.

There is an episode that sheds light on Adams’s initial political tendencies. As mentioned in the previous section, Clennel Wickham, the dissident journalist at the newspaper “Herald” who argued on behalf of non-whites and the poor in Barbados, was sued for libel due to his articles. The plaintiff was a rich white businessman who was singled out in Wickham’s articles denouncing the disparity of wealth on the island. The young, talented lawyer who represented this white businessman was none other than Grantley Adams. Wickham left the island after his loss in court, and the Herald was forced to go out of print.

Adams later on gained the nickname “Moses” due to his role in leading the public on Barbados’ path to independence. Current Barbados’ only international airport bears his name—the “Grantley Adams International Airport”. In other words, Grantley is Barbados’ national hero who opened the path towards its independence.

However, fresh out of Oxford, the privileged Adams was part of Barbados’ white conservative establishment which placed importance on the long-established ruling order, rather than a non-white leader of the masses. This is the start of Adams’ path, which varied greatly than that of Charles Duncan O’Neal, also returned from Britain, who teamed up with Clennell Wickham, committing himself to the labor union movement from the outset.

The change in Adams’ political tendencies became evident after 1934 when he was elected into the House of Assembly. By that time, Adams had no trouble making his way up in colonial society hierarchy despite being a man of color. However, his entrance into the political world controlled by the white conservative class is what possibly made him wake up to the reality of the hardships that his fellow non-whites were facing.

During this period, the 1937 Riots took place. Adams was the lawyer who represented Clement Payne, the man who was accused of igniting the riots and eventually exiled from Barbados. Even at this time, however, it seems that Adams still had hesitations; looking at various writings from the time, it appears that the people around him anticipated this capable Black lawyer to represent Payne, and reluctant Adams was pressured into taking the case.

Looking at how the deadly riots ended, Adams seemed to have prepared himself for the fight ahead, realizing that in order to overcome racial discrimination and improve living conditions, order and peace must be maintained while simultaneously meeting the needs of the general masses, instead of fanning the flames or using uncontrolled mass movements. This is how Adams actively became involved in political movements to improve the social status and living conditions of his fellow non-whites. During this process, there is no doubt that the voices and anticipation of those around Adams helped encourage him, who was just as, no, in fact who was even more knowledgeable, well-educated, and eloquent than the elite white ruling class.

Some Barbadians may oppose, but I am of the opinion that at this point what Adams was aiming for was the overall improvement of citizens’ lives and stability of the colonial society, and he did not yet have in his mind a clear picture for Barbados’ independence. Although independence movements in British colonies were occurring in Asia and Africa, Britain’s largest colonies India and Pakistan did not achieve independence until 1947—after World War II ended. British African colonies such as Sudan and Ghana did not become independent until some further ten years later (note 5). The majority of Britain’s West Indies colonies, including Barbados, were small powerless islands where getting in touch with the outside world and replenishing supplies were not easy, with no place to run in times of trouble. For them, independence still seemed like just a daydream.

(Grantley Adams)

(Barbados’ gateway to the sky, Grantley Adams International Airport)

Adams, who became the leader of the Barbados Labour Party (BLP), together with fellow party members Hugh Cummins and Wynter Crawford, created the party’s policy statement.

We can observe the statement was strongly influenced by socialist ideology, placing importance on the equal distribution of wealth. It emphasized that “the wealth produced in Barbados would not be equitably divided until the resources of wealth are owned and controlled by the Government on behalf of the community”. Specifically, it outlined public ownership of sugar plantation facilities larger than a certain size, securing a minimum wage, introducing a pension scheme, making compulsory education free, promoting increased supply of housing in order to get rid of the slums, among other ideas.

With the tail winds of the labor union movement in mainland Britain and the British West Indies colonies blowing in its favor, a labor union law was also passed in the Barbados Parliament in 1939. In the House of Assembly elections of 1940, the BLP won five seats out of 24, including Adams. The following year the “Barbados Workers’ Union (BWU)” was formed, with Adams as President and with young Hugh Springer (1913-1994) as General Secretary. At this point, the BWU was in effect the BLP’s “Labor Union Bureau” (note 6).

At this time, the Governor sent from the suzerain Britain to Barbados was Sir Grattan Bushe. Bushe, who understood that the political climate in the island no longer made it possible to ignore the BLP, added Adams to the “Executive Committee”. This Committee was founded at the end of the 19th century by Conrad Reeves, “the man of compromise”. In section 8, I talked about how the committee became a body that played the de facto role of “colonial government”. It took until then for the first non-white member to be added to its ranks.

Under Adams, the BLP expanded its political power with the influence of the BWU in the background, and subsequently won nine seats in the House of Assembly election of 1946. The BLP formed a coalition with the new political party, West Indian National Congress Party (note 7), which won seven seats, finally giving them the majority of the House.

Observing this, Governor Bushe gave Adams the responsibility of choosing four new members to join the Executive Committee. Committee members were each responsible for important administrative areas, such as finance, public safety, etc. In reality, their roles were similar to these of cabinet ministers. In other words, Barbados introduced the same type of system as nations with constitutional monarchies or countries with a symbolic presidential system; a cabinet was formed by the majority Assembly leader who was entrusted by the Head of State. Bushe’s process of gradually developing the self-governing colonial government’s systems is called “Bushe’s Experiment”.

The Process to Universal Suffrage

It is obvious that as the trend of the time, the gravity was to shift from the monopoly of wealth and power that the island’s white wealthy minority held towards the majority non-white and working classes. However, restriction of suffrage was an obstacle to executing this shift of power.

In the span of nearly two centuries since the establishment of Barbados’ House of Assembly, whose members were elected by colonial residents, in 1639 by Governor Hawley (Section 2), only wealthy, white men of British descent who were 21 years of age or older and who were landowners of a certain size and paid taxes over a certain amount, were allowed the right to vote and to be elected. Suffrage was conditionally expanded in 1831 to include Jewish men and a limited number of non-white men.

Thereafter, the struggles of Samuel Jackman Prescod and Conrad Reeves in the Assembly proved fruitful in 1884 when criteria for granting voting rights were significantly relaxed. However, even with the improvements, the number of citizens on the island who had voting rights was 1,604—amounting to only one out of 100 people of the total population (note 8). Gaining the right to vote in Barbados was no simple task.

While reforms were being made after the outbreak of the 1937 Riots, in 1943 during World War II, conditions limiting the right to vote were again relaxed even further. Women who met the new criteria were now allowed the right to vote. In 1950 after WWII, all restrictions were eliminated to allow every citizen over 21 years of age, regardless of race, sex, assets, and amount of tax payment, the right to universal suffrage (note 9). Finally all obstacles had been removed preventing the majority of citizens access to voting rights since the end of slavery and long-held political control of the rich minority plantation owners and merchants.

The first election of Barbados’ House of Assembly held under the adult franchise system was in 1951, the following year of its introduction. Prior to the elections, the BWU led by Grantly Adams signed an agreement regarding profit distribution with the Sugar Producers Federation - in other words the group of predominantly white business owners. Additionally, agreements were made regarding a paid leave as well as a framework for wage negotiations. With these achievements, the Adams-led BLP achieved an overwhelming victory, winning sixteen out of twenty-four seats in the House.

Barbados and World War II

Grantley Adams’ chance to exert influence in the political arena of colonial Barbados overlapped with World War II.

Situated in the immediate south of the United States, at the entrance to the Gulf of Mexico, and surrounded by key strategic points such as the Panama Canal and the Trinidad and Venezuela oil fields, the Caribbean Sea was a strategically important area in the Atlantic during WWII. Numerous ports existed on colonial islands and protectorates of countries such as the United States, Britain, France, and the Netherlands. Thus the Caribbean Sea was a theater to naval battles against Axis Powers (Germany and Italy), which used submarines to carry out persistent attacks against the Allied Powers’ sea transport of oil and goods to and from the region.

Pointe-à-Pierre in British Trinidad was home to the UK’s largest oil refinery; Dutch colony Curaçao housed the Royal Dutch Shell Company’s oil refinery facility—the world’s largest at the time. The start of World War II increased the importance of oil from Trinidad and Venezuela for the Allies, as Italy blocked oil shipping from the Middle East through the Mediterranean.

Even Barbados, which did not possess any oil resources, was caught in the crossfire of a German attack. On September 11th, 1942, the Canadian steam merchant ship Cornwallis was anchored in Carlisle Bay when it was torpedoed by a German submarine U-boat 514. Nets had been strung in the bay to prevent the intrusion of submarines, but they failed to protect when the torpedo fired from the U-boat outside of the nets went right through and hit the Cornwallis, opening a hole in its hull.

There is a passage depicting this event in the previously introduced George Lamming’s autobiographical novel “In the Castle of My Skin”.

< Shortly after four o’clock one afternoon a large merchant ship was torpedoed in the harbour. The city shook like a cradle and the people scampered in all directions. The war had come to Barbados. Many of us flocked to the pier in hope of seeing the submarine. The shells made a big booming noise and spectators ran wild with hysteria. They ran a few yards away and ran back as quickly in the hope of seeing the submarine. The ship’s hull sank slowly below the surface and most of us had our first experience of seeing a ship go down….. But it was only natural in a war that the Germans should do what they did. If Barbados said she was Little England she had to put up with what she got for being what she was. Moreover, it was rumoured that when the Prime Minister of England announced the declaration of war the Governor of Barbados, at the request of the people, sent the following cable: ‘Go brave big England for Little England is behind you’…. >

The Cornwallis was anchored in shallow water and thus it did not sink but rather was run aground on the ocean floor. It was subsequently repaired and was ready to sail again. However, the Cornwallis was ill-fated. Two years after the Barbados attack, it was once again torpedoed by a German submarine offshore the U.S. state of Maine. This time the damage was irreversible and it was not able to make a comeback.

Errol Barrow’s Return to his Home Island

A few years after the Allied Powers’ victory of WWII, when Grantley Adams was on the fast track in his colonial political career, the young Errol Barrow (1920-1987) returned home to Barbados from the UK. Twenty-two years Adam’s junior, Barrow was a naval navigator for the British air force, and came back home after receiving higher education in Britain after the war.

Barrow, who was Adams’ comrade, later his political rival, and later the first Prime Minister of independent Barbados, affectionately called “the Father of Independence”, was born to a Black family in St. Lucy Parish in the northernmost part of the island. His father, Reginald Barrow, was a reverend of the Anglican Church in Barbados and the U.S. Virgin Islands. However, no matter where he went, the Reverend ended up rubbing his superiors and wealthy white patrons of the church the wrong way, and in the end he converted to the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) (note 10) and moved to New York.

This forced his wife, Ruth, to take her five children with her and move into her parents’ home in Bridgetown. During his childhood living at the O’Neal house with his siblings, Errol Barrow often played with his cousin, the previously mentioned Hugh Springer, who lived in the neighborhood. Also, Ruth’s brother (Barrow’s uncle), Charles Duncan O’Neal, had already formed the “Barbados Democratic League” and his political activities were in full swing (refer to Section 8). It is not hard to imagine that Springer and O’Neal played an influential role in Barrow’s future political aspirations.

WWII started in Europe right around the time Barrow graduated from high school. I mentioned in Section 8 the anecdote of Barrow’s departure from Barbados after enlisting in the suzerain Britain’s military service in 1940. That year Barrow left for the UK along with twelve other Barbadian men.

After being assigned to the Royal Air Force, Barrow first trained in wireless operation in Britain, then was stationed in Canada to undergo navigation training, and returned to Britain to become a Navigator Sergeant of fighter planes. Subsequently, Barrow took part in over 50 actual combat scenes on the front lines of the war between the Allied Powers and the German Nazis in Europe, including the Battle of Arnhem and the Battle of the Bulge. He survived the war and was eventually promoted to Flying Officer. Among the twelve cohort Barbadian soldiers, he as one of six who made it back home alive.

After the war, Barrow left the military and with his scholarship for colonial ex-servicemen matriculated at the Inns of Court and the London School of Economics (LSE) concurrently.

Barrow’s leadership skills were already recognized around this time; he was elected Chairman of the “Council of Colonial Students” at LSE. I personally believe that Barrow’s time at LSE greatly influenced his world view and future. Forbes Burnham, the future first Prime Minister of Guyana after its independence, and Michael Manley, future Jamaican Prime Minister, were among students from British Caribbean colonies studying alongside Barrow at LSE. Additionally, Lee Kuan Yew, the first Prime Minister of Singapore after its independence who led the nation for about 30 years, was also in attendance at the same time (note 11). Right around this time, India and Pakistan had finally gained independence from Britain after a long decolonization struggle with the suzerain. We can imagine that Barrow and his fellow comrades had passionate talks with each other about their dreams of independence for their respective homelands.

The year was 1950 when Barrow returned to Barbados with high ambitions after graduating from LSE and the Inns of Court with excellent grades and lawyer’s qualification.

(Errol Barrow (second from left) during his time in the British Airforce)

(Note 1) The design of Barbados’ national flag was an open contest right before the island gained its independence. Grantley Prescod, a high school art teacher, won the design contest and his idea subsequently became the design of the current national flag of Barbados.

(Note 2) Soon after the formation of the Barbados Labour Party (BLP), it changed its name to “Barbados Progressive League”, and continued activities under this name for several years, until it changed its name back to Barbados Labour Party. In order to avoid confusion, I will continue to refer to the Party as the BLP.

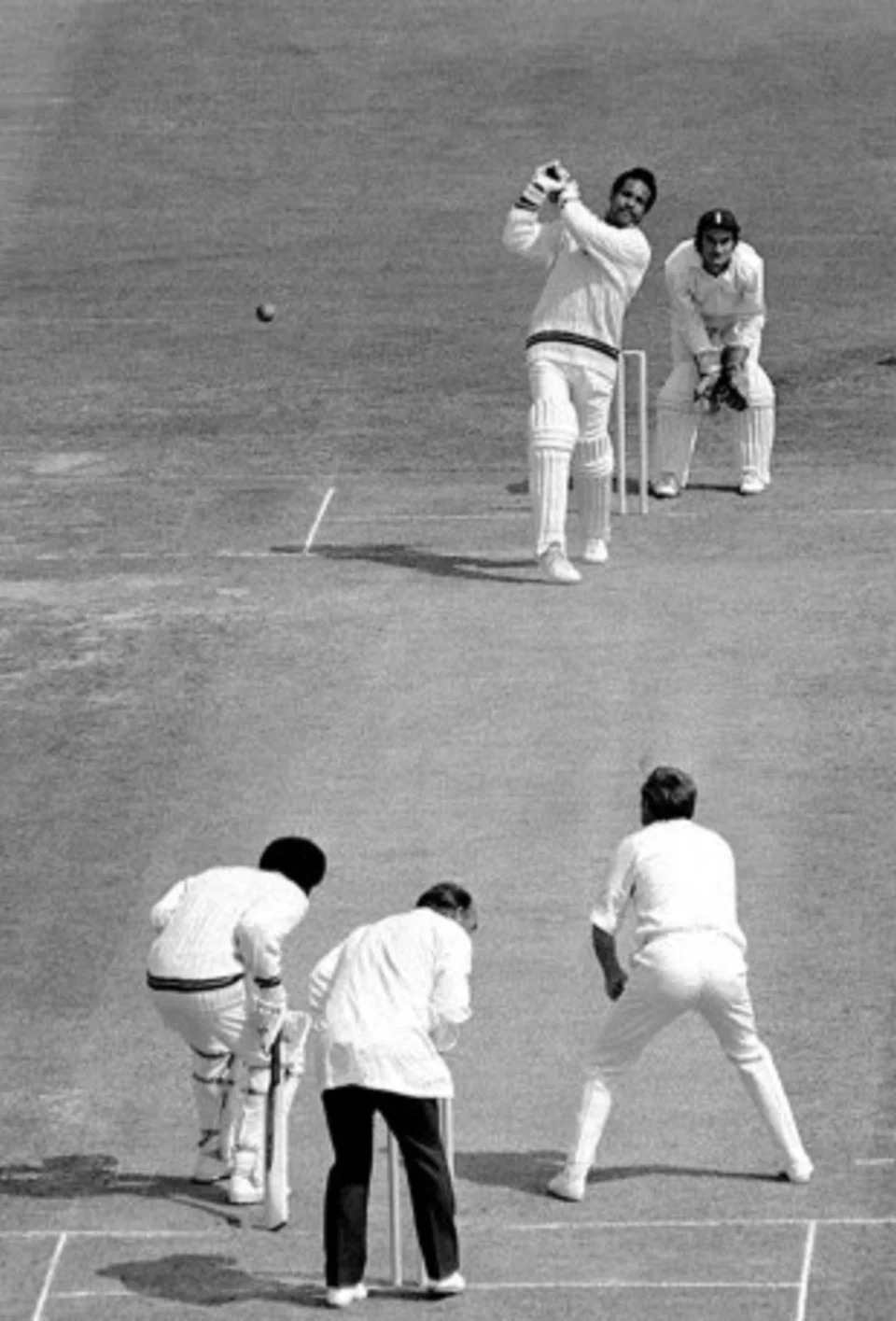

(Note 3) Cricket is still the most popular sport today in Barbados, where British rule lasted for the majority of its history. One of the eleven Barbados National Heroes is Garfield Sobers (b. 1936), a legendary cricket player of Barbados whose name is known throughout the British cultural spheres in the world.

I had the opportunity to watch a cricket match while I was in Barbados. Knowing, however, nothing about the sport and its rules, I found it difficult (to say the least) to understand what was so interesting about this too-long-lasting game as I was surrounded by wildly enthusiastic fans on all sides.

(A cricket game (Garfield Sobers in batting position))

(Note 5) Before Britain’s Asian and African colonies gained their independence, British dominions of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Ireland, and Newfoundland became completely sovereign from Britain under the Statute of Westminster in 1931. However, it is worth noting that all of the above-mentioned dominions had been “white” semi-autonomous territories. The Statute of Westminster marked an end to the British Empire, creating in its place the British Commonwealth.

(Note 6) Frank Walcott (1916-1999) assumed the BWU General Secretary post in 1947 when Hugh Springer moved to Jamaica to help with the founding of the University of West Indies. Walcott continued to hold top positions in the BWU for about fifty years. He led the process of separating the BWU from the BLP, as the government had become the nation’s largest employer after Barbados’ independence. Grantley Adams held the position of President of the BWU until 1954. Hugh Springer and Frank Walcott stand alongside Grantley Adams as three of Barbados’ National Heroes.

(Note 7) The West Indian National Congress Party (called the Congress Party) was founded in 1944 by Wynter Crawford after parting with Grantley Adams and the BLP, of which Crawford was also a founding member. The Congress Party was more radical than the BLP, with its proposal to disestablish to the Anglican Church, among others. The Congress Party was effectively abolished when Crawford joined the Democratic Labour Party (DLP) founded by Errol Barrow in 1955. It is evident that the Indian National Congress, which led the Indian independence movement around this time, influenced the naming of the West Indian National Congress Party.

(Note 8) A-Z of Barbados Heritage, P.148

(Note 9) In 1962 the voting age was lowered to 18 years from the previous 21 years of age. Incidentally, male suffrage in Japan came in 1925, but women’s suffrage was not until after the end of WWII in 1945.

(Note 10) The AME is a Christian denomination founded at the end of the 18th century by African Americans after the independence of the United States in order to avoid racial discrimination. It is said that there are around two million followers of this denomination worldwide.

(Note 11) The gifted Singaporean student Lee Kuan Yew seems to have made a particularly deep impression upon Barrow. While in terms of land area Barbados and Singapore are more or less the same, Barrow focused on Singapore’s economic development under Lee’s leadership after it achieved independence. This is evidenced by one of Barrow’s last speeches in 1986, where he highly praised Singapore as a model of how to successfully build a nation.

(This column reflects the personal opinions of the author and not the opinions of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan)

WHAT'S NEW

- 2025.12.25 UPDATE

PROJECTS

"Barbados A Walk Through History Part 17"

- 2025.12.2 UPDATE

EVENTS

"Pacific & Caribbean Student Invitation Program 2025"

- 2025.10.30 UPDATE

EVENTS

"Support for the 2025 Japanese Speech Contest in Jamaica"

- 2025.10.30 UPDATE

EVENTS

"Invitation Program for the Director of Bilateral Relations of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade of Jamaica"

- 2025.10.16 UPDATE

EVENTS

"421st Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.9.18 UPDATE

EVENTS

"420th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.8.28 UPDATE

PROJECTS

"Barbados A Walk Through History Part 16"

- 2025.7.17 UPDATE

EVENTS

"419th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.6.19 UPDATE

EVENTS

"418th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.5.15 UPDATE

EVENTS

"417th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"