Barbados: A Walk through History (Part 10)

Section 6 Island Fortress of the East Caribbean (Cont'd)

(View of the Garrison Savannah)

Scramble for Colonies between Britain and France

Barbados, who had driven away a Dutch invasion, began to strengthen its defense in the event of threats from outside enemies. Fortresses armored with batteries began to be built on key southern to western locations on the island in areas such as Bridgetown, Holetown, Speightstown and others.

As Barbados’ suzerain, Britain, started to surpass Spain and the Netherlands for supremacy on the world seas in the 18th century, it’s strongest rival in the scramble over colonial land to emerge was Louis XIV’s France.

In 1701, the War of the Spanish Succession began when Louis XIV meddled in Spain’s royal succession affair, dragging all of Europe into it. In the confusion of the moment, England and France engaged in competition for the Caribbean and North American colonies, while battles were simultaneously being fought on the European continent. This conflict between the two nations is called Queen Anne’s War (note 1), named after the Queen of England at the time. England dominated the war on the North American continent, ousting the French and securing its foothold in Canada, such regions as Acadia, Newfoundland, Hudson Bay which were under French control. However, the final winner of the Caribbean battles was left in a vague state.

Just by looking at the dizzying rate at which the islands belonging to the Lesser Antilles- St. Kitts, Nevis, Guadeloupe, Montserrat, Dominica, Martinique, St. Lucia, St. Vincent, and Grenada- changed ownership between England and France, one can tell how intense the competition for colonial domination was throughout the 18th century.

Barbados was an outpost for the English fleet’s attacks on neighboring enemy’s islands, and thus it continued to strengthen its defense armed like a hedgehog. Around the year 1730, this small island had 22 forts equipped with 463 cannons, and a total of 4,000 infantry and cavalry.

Garrison Savannah

At the height of Queen Anne’s War in 1705, in the outskirts of Bridgetown overlooking Carlisle Bay from upon a hill, construction of St. Ann’s Fort began and lasted for more than a decade. The island’s military facilities were centered around this sturdy stone fort. In front St. Ann’s Fort was a parade ground, which served as Barbados’ militia garrison, and was surrounded by military barracks, armory, hospital, prison, and other buildings.

The English fleet occasionally arrived at Barbados, but it was not until much later, during the American Revolution, in 1780 that the navy of Great Britain had a permanent station on the island. The area used for military practice and its encompassing buildings began to be called “Garrison Savannah”, and it continued to exercise its authority over the East Caribbean region as the British headquarters until the troops’ withdrawal in 1905. Sandwiching Bridgetown, on the other side of Garrison Savannah was Queen’s Park, where the official residence of the Commander of the British troops for the Eastern Caribbean rested (note 2).

Centuries later, when Barbados achieved independence from Britain on November 30th 1966, Garrison Savannah was the site of the raising of the Barbados national flag after the UK’s Union Jack was taken down.

In 2011, the Garrison, along with the old Bridgetown city center, was registered as a UNESCO World Heritage Site under the title of “Historic Bridgetown and its Garrison” in order to preserve and pass on the testament of the spread of Great Britain’s Caribbean colonial empire, thus enabling the Garrison’s view to remain practically unchanged to this day. A handful of the main buildings are still used for Barbados’ Defense Force headquarters; the previous parade ground turned into a horse race track, the prison turned into a museum, while the open lot in front of St. Ann’s Fort was of all things turned into a parking lot.

(The Drill Hall-one of the buildings on site at the Garrison Savannah. Built in 1790, it was used as barracks by the British military, and is currently the site of Barbados’ Defense Force.)

(Present St. Ann’s Fort)

There is a colonial-style building standing adjacent to Garrison Savannah. The building was named “Bush Hill House” was used to house high-ranking officers. One of the more remarkable residents, from the beginning of November 1751 for approximately six weeks, was a young George Washington, future first president of the United States of America.

Presently, the site’s name has been changed to the “George Washington House”, complete with an on-site restaurant. It has become a popular tourist destination for cruise passengers (particularly Americans) enjoying the history and beauty of the property.

Presently, the site’s name has been changed to the “George Washington House”, complete with an on-site restaurant. It has become a popular tourist destination for cruise passengers (particularly Americans) enjoying the history and beauty of the property.

But why such hype over a place where a future president stayed for a mere six weeks? In fact, Washington left North America only once during his entire lifetime-and the place he visited was the island of Barbados.

Washington, at the age of 19, along with his half-brother Lawrence arrived on the island by ship from their hometown Virginia. Lawrence suffered from tuberculosis, and his doctor advised him to change his surroundings and recuperate in a place with better climate. Washington was taken along with his older brother to the warm island, which was chosen not only for its health benefits, but also because they had distant relatives who had immigrated from England and were a prominent family in Barbados.

Washington wrote in his diary the following about his stay in Barbados:

“…we pitched on the house of Captn. Croftan commander of James Fort…the sea is about a mile from town (Bridgetown) the prospect is extensive by land and pleasant by sea as we command the prospect by Carlyle (Carlisle) Bay & all the shipping in such manner that none can go in or out without being open to our view.” (Note 3)

Although Washington was there as his brother’s aide, it seems he enjoyed his time on the island, acquiring a taste for rum and such. However, during his month-and-a-half stay he was exposed to smallpox, not an uncommon disease at the time. Despite his case being mild, Washington was left with a few pockmarks on his face.

However, no one knows what life has in store for them. Over 20 years later during the start of the American Revolution, troops under General Washington’s command became infected with the smallpox. Many soldiers lost their lives from this outbreak (note 4), but Washington, who had previously been exposed to smallpox in Barbados and was immune to the disease, was able to survive the outbreak and become the first president of the United States after its independence from England.

His brother Lawrence who suffered from tuberculosis died a few months after returning to Virginia from Barbados, and thus it seems the stay on the island did not have much benefit in the end. However, what if the younger brother, George, had never visited the island and been exposed to the smallpox? What would have become of America’s revolution? There is an anecdote that I have heard in Barbados that says “Therefore, George Washington, to celebrate his new role as President of the United States, ordered a barrel of Barbados rum”, which might just in fact be true (note 5).

On the subject of dubious, one of the slogans of the American Revolution “No Taxation without Representation” was used by the colonists to protest the taxation of the colonies without them being allowed a representative in parliament back in England. The spirit of this slogan was incorporated into the Declaration of Independence. However, over 120 years earlier when the Charter of Barbados was signed in 1652 upon the Barbadian colonists’ submission to their suzerain English naval fleet, it stated that “no taxes, customs, imports, loans, or excise shall be laid, nor levy made on any the inhabitants of this island without their consent in a (Barbadian) General Assembly” (Part 4 Section 3 “The Island Tossed About by War”). In other words, the idea “no taxation without representation” was already alive. There are theories which stir our imagination stating that this idea of “no taxation without representation” was pounded into the young Washington’s head during his short time on the island (note 6). Do any of these seem plausible?

(The George Washington House)

When Washington was fighting in the Revolutionary war in 1778, France entered the war in North America on the side of the 13 colonies in order to defeat its sworn enemy, Britain.

The aftermath of France’s decision was immediately seen in the struggle for dominance in the Caribbean. In the eastern Caribbean where British naval presence waned due to the need for support in suppressing the American Revolution, Dominica, St. Kitts, St. Vincent, St. Lucia, Grenada etc. fell into the rule of French hands. Britain continued trying desperately to hold onto its control over Jamaica, Antigua, and Barbados. As previously mentioned, permanent military forces were placed on Barbados in 1780 as Britain struggled to maintain its hold on the region.

In 1782, France attempted to invade Jamaica. However, Admiral George Rodney of the British navy prevented any such attempt of invasion of its colony in his win of the Battle of the Saintes, which took place offshore Dominica.

There was a temporary lull on the Caribbean front after this battle between the two enemies, but fighting would flare up again with the start of the French Revolution in 1789 and the ensuing Napoleonic Wars.

Ripples of the French Revolution were first seen in the French colony Saint-Domingue on the island of Hispaniola.

In 1791 with the onset of the French Revolution, Saint-Domingue experienced uprisings occurring from the Mulatto and African slave population who were inspired by revolutionary ideals imported from France. The leader of the rebelling slaves was Toussaint Louverture, who was caught and later died imprisoned by the French army. However, his followers fought against not only the French, but also the English and Spanish troops who intruded in Saint-Domingue, eventually creating the Republic of Haiti in 1804.

Haiti’s success of breaking free from the chains of slavery and becoming an independent nation inspired slave-driven movements for freedom in colonies all over Central and South America and the Caribbean.

On the other hand, back on the European continent, fearing the fall of the French monarchy, Austria and Prussia intervened in the French Revolution, and with the execution of Louis XVI in 1793, Britain also stepped into the war.

When Napoleon appeared following the upheaval of the French Revolution, France began attacking not only the European continent, but all areas of the world where its rivals, especially Britain, had colonies. As part of his strategy, Napoleon did in the Caribbean exactly what the Dutch had done in the Anglo-Dutch wars-force the English navy to disperse its fleet by opening a new battlefront in the Caribbean.

In the spring of 1805 under orders from Napoleon, a French fleet of18 ships led under Admiral Pierre-Charles Villeneuve set sail for the Caribbean Sea.

British Admiral Nelson’s Entrance on Stage

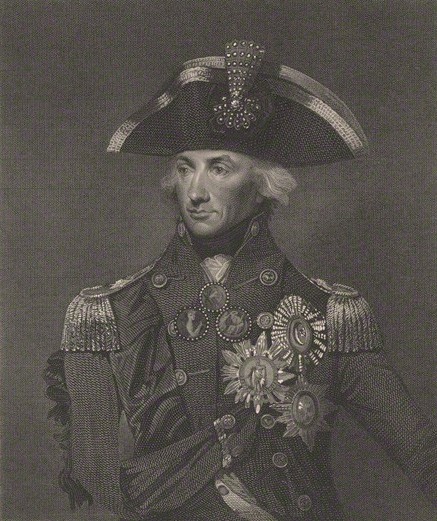

A British fleet of 18 vessels followed after Villeneuve’s ships, led by Admiral Horatio Nelson.

Nelson, who is said to be one of Britain’s best military strategists in history, was born into a poor family in the English town of Norfolk in 1758. Poverty forced him to enroll in the navy at the young age of 12. He had many encounters with the Caribbean in his lifetime, being stationed on the islands of Jamaica and Antigua in his late 20s, and he also met and married his wife on the island of Nevis.

While continuing up the ladder to fame in the navy, Nelson distinguished himself against others in naval exploits around the world by showing a disregard for danger and courageous tactics at war. However, his bravery cost him his right eye and right arm, making him a one-eyed one-armed officer.

Nelson’s claim to fame was at the Battle of the Nile in 1798 when he was able to defeat the French forces, temporarily isolating the seemingly unstoppable Napoleon in Egypt. Incidentally, as fate would have it, Villeneuve was one of the commanders in the French fleet who just barely made it out of the attack alive.

This time the fleet headed by Villeneuve was sailing towards the Caribbean, anchoring approximately 240 kilometers north of Barbados in the French colony of Martinique. There is a widely-believed theory that Villeneuve was planning an attack on the further north British colony of Antigua at this time.

The pursuing Nelson most likely figured that Villeneuve would aim for Barbados, British stronghold of the eastern Caribbean. Nelson’s fleet sailed into Carlisle Bay, waiting for the enemy to approach. Inhabitants of Barbados, being aware that Villeneuve’s fleet was on its way for them, were absolutely frightened, and so they wholeheartedly welcomed Nelson’s presence. However, any anxiety or anticipation felt for the approaching battle evaporated as Villeneuve’s fleet never approached Barbados nor Antigua, but instead turned around and headed back to European waters by way of the Atlantic.

These were days long before radar and GPS satellites. Nelson, having no idea where his enemy was hiding, left Carlisle Bay and headed in the opposite direction of Villeneuve-to the south towards Trinidad. Bad information claiming Villeneuve had taken this route is said to be blamed for Nelson’s move. Nelson returned to the battle scene in Europe after realizing his enemy had left him behind in the Caribbean. A few months later, Nelson and Villeneuve had a showdown at sea offshore Cape Trafalgar of Spain, where Nelson and his fleet waited vigilantly for Villeneuve to show himself.

(Admiral Nelson)

The Battle of Trafalgar was fought between the British naval fleet led by Admiral Nelson, and the combined French and Spanish navies under the command of Admiral Villeneuve on October 21st, 1805. The battle, which still stands out as one of the greatest in the pages of history, extinguished any hope Napoleon had of assaulting the British homeland.

Nelson, commanding his fleet on the flagship Victory, outnumbered by the French and Spanish fleets, used a bold and daring tactic called “the Nelson Touch” to defeat the enemy. The seemingly reckless move was to divide the fleet into two wings and penetrate into the center of the enemy’s single-file placed fleet.

The British fleet succeeded in crushing the French. However, ignoring his subordinates’ advice for him to hide in a safe place, Nelson directed his fleet from the top deck, ultimately dying from gunshot wounds sustained in battle. Villeneuve, on the other hand, was taken prisoner by the British.

“Thank God I have done my duty” exclaimed Horatio Nelson, before his death, and subsequently becoming savior and national hero of England.

Britain was not the only land celebrating the win at Trafalgar while deeply mourning Nelson’s death. Barbados, who only a few months previously Nelson’s fleet had docked at, was also simultaneously celebrating and mourning. What was most likely on their minds was the thought that “if the Admiral hadn’t made his way to the Caribbean, we might’ve been taken over by the French”.

The idea of erecting a bronze statue in honor of Admiral Nelson gained traction in the circles of the wealthy English ruling class of Barbados. Within a few weeks of fundraising a total of £2,300 was subscribed to erect Nelson’s statue in Bridgetown, 1813.

Nelson’s Column, a monument dedicated to the Admiral, glaring at the direction of France, is located in the aptly-named Trafalgar Square in London. Compared to its counterpart in England, the statue in Barbados may seem underwhelming, but it was erected 30 years prior to the one in Trafalgar Square, giving a good idea of how popular Nelson was in Barbados at the time.

The statue dedicated to the admiral who “never once lost to Napoleon” became the symbol of Bridgetown.

As for the defeated French Commander Villeneuve taken prisoner by the British in the end of the Battle of Trafalgar, he was released a year after his capture and returned to France. However, he was soon found lifeless in a room in a small inn in Rennes, Brittany. It is thought that he committed suicide, but there are theories that in fact Napoleon ordered Villeneuve’s murder.

We must always be on guard when we look back at history and question “what if…”. But just what if Nelson and Villeneuve had encountered each other in the Caribbean and engaged in battle, forever altering the region’s future and rewriting its history?

Getting back on track, the defeated Napoleon tried to get revenge for his loss against Britain by ordering the “Berlin Decree” in 1806. By forbidding France and its allies to trade with Britain, Napoleon hoped to deal a devastating blow to the British economy.

The Berlin Decree, however, turned out to be counter-effective. The decree numbed the economies of the many countries in Europe that depended on Britain for trade, generating strong anti-Napoleon sentiment among them, eventually leading into the Battle of the Nations (Battle of Leipzig) and Napoleon’s downfall.

On top of Napoleon’s failure to predict Britain’s resilience, he turned a blind eye to other nations’ needs and concerns when enforcing sanctions against Britain. This was the beginning of the end for Napoleon’s reign over Europe. Needless to say, Britain sustained damage to its economy, but the rest of Europe was also worn out economically. In order to overcome the stagnant situation, Napoleon’s army tried to invade Moscow but instead of coming back valiant heroes like in the past, this time they came home beaten and broken. There are actually some very interesting points when comparing this situation to current world events.

Signal Stations

At any rate, Barbados, who had just nearly escaped from a French invasion, became increasingly concerned about its self-defense ability.

In regards to this vital concern, observation towers called “signal stations” were constructed around the island. This idea is credited to the Governor Stapleton Cotton, 1st Viscount Combermere who came up with the proposal in 1817. Combermere, who had extensive military experience and understood the importance of transmitting information quickly, ordered the construction of six signal stations on elevated terrain around the island by the year 1819 (note 7).

The stations were constructed so that they overlooked the immediate land and sea, as well as had the other stations in sight. When a suspicious ship entered into view or any other emergency situation, signal flags and flag semaphore could be immediately used to alert the entire island. British troops stationed on the island were in charge of manning and overseeing the stations, while land provision, construction, and repairs were undertaken by the colonial authorities. However, these signal stations had another important role aside from protecting the island against invaders-preventing slave revolts.

Bussa’s Rebellion mentioned in section 5 occurred a year before Combermere became Governor. The revolt, which shook the island to its core, was one of the disturbing movements in the Caribbean as a whole after the shock of Haiti gaining its independence through slave uprisings. It was only natural that the white ruling class of Barbados strengthened their watch over the slaves’ movements considering the aftermath of Bussa’s Rebellion.

One of these signal stations still exists today-Gun Hill Signal Station, located almost in the center of the island in St. George Parish. It has been preserved and is open to visitors. From the lookout one can get a 360-degree view of the surrounding area, and peering into the binoculars one can slip back in time and imagine how watchmen could easily track people moving around down below, or unusual changes in the sprawling sugarcane fields.

The signal stations came to play another unexpected role on the island. At the time smallpox, yellow fever, cholera, and other infectious diseases were occasionally going around the island, and when an infection occurred in crowded barracks at the Garrison Savannah, the soldiers were split up and sent into a form of quasi-quarantine at the signal stations.

The signal stations, which contributed to the island’s safety and security, were put out of a job by the end of the 19th century with the induction of Morris Code and telephones, which had also made their way to Barbados.

(Gun Hill Signal Station)

*********************************************

On November 16th, 2020, during my stay in Barbados, a memorable event happened-Admiral Nelson’s statue, which stood in National Heroes Square right in front of the Barbados Parliament in central Bridgetown, was taken down upon the decision of the government.

Prime Minister Mia Amor Mottley made the following comment on the removal of the statue:

“The removal of the statue is merely a symbolic act. It is first and foremost a symbol that we are ready to take other steps in the development of our nationhood…The conversation about identity and culture needs to continue. Also, the conversation around new forms of slavery and discrimination need to be had for progress and greater unity.”

br /> The calls to remove Nelson’s statue had existed in Barbados for a while, with a sharp rise in the 2000s.After several decades of the independence of Barbados, formerly held up by African slaves, its predominantly Black population began asking the lingering question of “what meaning does this British guy’s statue hold for us, sitting in the center of the capital, looking down on us?”.

There is no mistaking that Admiral Nelson was an outstanding naval officer, but gradually the feeling that “Nelson, a soldier of the British Empire, was a person who embodied colonialism and racial discrimination of our former suzerain that enjoyed the wealth and prosperity created through the slave trade and slave labor. So, his achievement should not be extolled for us and for our ancestors” became more prominent.

Nelson’s statue was sometime vandalized during the night in the past few years, the culprit most likely influenced by the above sentiment growing in Barbados (I have not heard anything regarding discovery of suspects responsible for the defacing).

Although anti-Nelson sentiment was growing, there were also voices against the removal of the statue. Taking a look at the opinion column in the local newspaper, there were a variety of reasons for opposing dismantling the statue. “Nelson didn’t partake in the slave trade himself” or “He was doing what was expected of him as a navy officer in his day and time”, “If it weren’t for Nelson, Barbados might have become a French colony”, “The era when Nelson was active and the slave trade was ‘legitimate’ is also part of Barbados’ history, and we should be careful when considering what to erase”, as well as opinions solely looking at the practical gain: “If the statue is taken down, then the number of visitors from the UK will potentially decrease”, etcetera (note 8).

A large influencing factor on the direction of the debate on the future of Nelson’s statue was the Black Lives Matter movement, which was coming to a height in the US in May 2020, and subsequently spread all over the world (note 9). This movement made a large impact on the Black nation; in particular it acted as a catalyst in the increase of various Pan-Africanism groups’ activities (note 10). In line with this, support for the removal of the statue within Barbados accelerated, and the government made the aforementioned decision regarding its removal.

On the day the statue was removed, a pan-African organization hosted celebratory events in the vicinity. However, when the time came for the actual removal of the 200-year-old statue, it was performed solemnly without any disturbances. After standing in central Bridgetown for over two centuries, the statue was taken down and brought to the museum warehouse for preservation, marking the end of a chapter of Barbados’ history.

(To be continued in Section 7: The Path to Abolishing Slavery)

(Nelson’s Statue, which stood in central Bridgetown from 1813-2020)

(Note 2)This official residence is called Queen’s Park House, and currently houses an art gallery and small theatre.

(Note 3) The Writings of George Washington, vol.1, (1748-57)

(Note 4) At one point, the Continental Army pushed the British troops all the way to Quebec, but the smallpox epidemic caused them to stop short their attack. Major General John Thomas of the Continental Army, whom Washington relied on to command the troops in the Canadian offensive strategy, also died of the smallpox. During this time British support troops arrived forcing the Continental Army to give up their further advance, sparing Canada from becoming part of United States territory.

(Note 5) WEEKEND NATION, January 22, 2021 “US Ambassador toasts Biden-Harris moment”

(Note 6) The Military History of Barbados 1627-2007 by Major Michael Hartland, p.19

(Note 7) The six original signal stations were Gun Hill, Highgate, Moncrieffe, Cotton Tower, Grenade Hall, and Dover Fort. Later an additional five stations were built to encompass Bridgetown as well.

(Note 8) The removal of Nelson’s statue did not, in fact, have any effect on the number of British visitors, nor did it sour the relations between the two countries.

(Note 9) The height of the Black Lives Matter movement in this context refers to the protests that took place on an international scale in response to the murder of George Floyd by a white police officer in Minneapolis, Minnesota in May 2020. The officer kneeled on Floyd’s neck for over eight minutes, despite Floyd telling him he couldn’t breathe.

(Note 10) “Pan-Africanism” is a movement that aims to connect people from the African continent with other people from the Africa Diaspora in all corners of the world, releasing them from suppression and protecting their rights among others.

(This column reflects the personal opinions of the author and not the opinions of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan)

WHAT'S NEW

- 2025.12.25 UPDATE

PROJECTS

"Barbados A Walk Through History Part 17"

- 2025.12.2 UPDATE

EVENTS

"Pacific & Caribbean Student Invitation Program 2025"

- 2025.10.30 UPDATE

EVENTS

"Support for the 2025 Japanese Speech Contest in Jamaica"

- 2025.10.30 UPDATE

EVENTS

"Invitation Program for the Director of Bilateral Relations of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade of Jamaica"

- 2025.10.16 UPDATE

EVENTS

"421st Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.9.18 UPDATE

EVENTS

"420th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.8.28 UPDATE

PROJECTS

"Barbados A Walk Through History Part 16"

- 2025.7.17 UPDATE

EVENTS

"419th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.6.19 UPDATE

EVENTS

"418th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"

- 2025.5.15 UPDATE

EVENTS

"417th Lecture Meeting Regarding Global Issues"